Selecting only 40 first-wave feminists is hard enough but how is possible to round off such a list? Perhaps only by recalling one who, as a multi-faceted pioneer, crossed many different barriers and whose loving critique of the Church remains vital today…

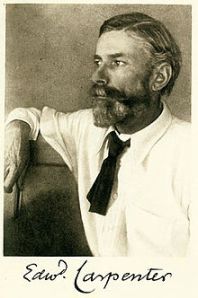

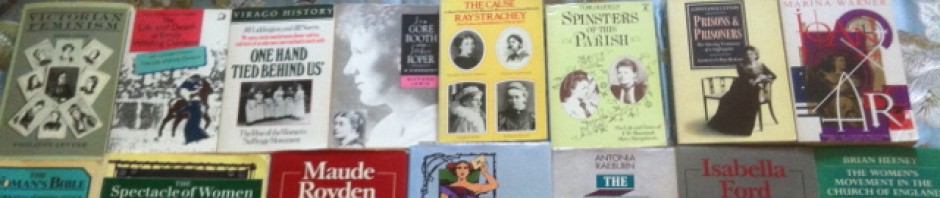

Maude Royden (1876-1956) was a remarkable woman who broke new ground for women (and as she saw it, thereby for children and men) in her leadership in the women’s and peace movements, in Britain and overseas, and, in thought and action, in leadership within the Church and in advocacy for a more healthy and reasoned approach to sexuality. Her legacy is impressive as is her continued challenge.

Maude Royden (1876-1956) was a remarkable woman who broke new ground for women (and as she saw it, thereby for children and men) in her leadership in the women’s and peace movements, in Britain and overseas, and, in thought and action, in leadership within the Church and in advocacy for a more healthy and reasoned approach to sexuality. Her legacy is impressive as is her continued challenge.

Born in Mossley Hill, Liverpool, daughter of Sir Thomas Bland Royden, Maude Royden was educated at Cheltenham Ladies School and Lady Margaret Hall in Oxford. She obtained what she called her ‘suffrage education’ however through her work at the Victoria Women’s Settlement in Liverpool. Although she went on to parish work at South Luffenham, and to University Extension Lecturing, she could never shake off her confrontation with the plight of poor women, and its implications. By 1905, the year in which militant tactics really began to reignite the suffrage movement, she was ready to begin her suffrage career. The leading Church feminist of her day and a founder member of the Church League for Women’s Suffrage, as a suffrage speaker and executive member for the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and later as editor of the NUWSS journal The Common Cause, she had few equals. A major refrain of her speeches and writings was the linkage between suffrage and social reform.

With the outbreak of war, Maude Royden then began her deep commit ment to peace work. She became the secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (which still continues 100 years after its foundation) and actively campaigned at great risk to her health and safety. Although unable to travel to the women’s peace congress in the Hague in 1915, when the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom was established, she also became its vice-president. She was a strong supporter of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which, founded by Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, encouraged men to:

ment to peace work. She became the secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (which still continues 100 years after its foundation) and actively campaigned at great risk to her health and safety. Although unable to travel to the women’s peace congress in the Hague in 1915, when the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom was established, she also became its vice-president. She was a strong supporter of the No-Conscription Fellowship, which, founded by Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, encouraged men to:

refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred.

Further impelled by the horrors of the first world war, Maude Royden was a major voice for peace before the second world war. Indeed, responding to invites, she made several international tours, in the USA, Japan, China, Australia and New Zealand, speaking about the League of Nations, social justice, the ministry of women and Christianity. She was the prime mover in the inter-war attempt to form a Peace Army of unarmed passive resisters to intercede between the combats in the world’s military confrontations, starting with the one in Manchuria. In 1934 she visited India and met Gandhi. When Dick Sheppard, a canon of St Paul’s Cathedral, formed the Peace Pledge Union (PPU), she was also one of many distinguished figure who joined what became a significant mass movement (and which remains the oldest secular pacifist organisation still in existence in Britain). However, on the outbreak of the Second World War Maude Royden renounced pacifism, as she accepted that it was necessary to fight against the evils of Nazism.

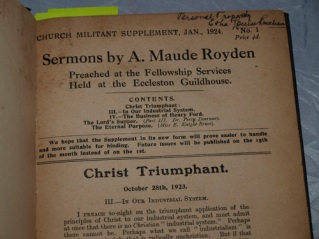

Maude Royden might also have had a successful political career. In 1922 she was indeed invited by the Labour Party to stand as its candidate for the Wirral constituency but declined because she wanted to concentrate on her religious work. For, though disappointed by the lack of Anglican women’s ordination in her lifetime, she was a major contributor to the track. This began in 1917 when she accepted an invitation to become assistant preacher at the City Temple in London, being thus the first woman to occupy this office (though not, as she pointed out, the first woman to speak there: the Salvation Army co-founder, Catherine Bramwell-Booth having that distinction). Roundly denounced by some as a triple horror – ‘a woman, a pacifist, and an Anglican’ (!) – she was warmly received by others, and supported by many Anglicans, including Bishop Edward Hicks (who attended her first Sunday preaching). Indeed, though Maude herself admitted to him that she had a had a ‘severe shock’ in her ‘Anglican soul’ about pronouncing a benediction in his presence, he simply replied ‘it was the best blessing I have had since my mother died.’ (Bid Me Discourse, A.M.Royden Papers).

Maude Royden might also have had a successful political career. In 1922 she was indeed invited by the Labour Party to stand as its candidate for the Wirral constituency but declined because she wanted to concentrate on her religious work. For, though disappointed by the lack of Anglican women’s ordination in her lifetime, she was a major contributor to the track. This began in 1917 when she accepted an invitation to become assistant preacher at the City Temple in London, being thus the first woman to occupy this office (though not, as she pointed out, the first woman to speak there: the Salvation Army co-founder, Catherine Bramwell-Booth having that distinction). Roundly denounced by some as a triple horror – ‘a woman, a pacifist, and an Anglican’ (!) – she was warmly received by others, and supported by many Anglicans, including Bishop Edward Hicks (who attended her first Sunday preaching). Indeed, though Maude herself admitted to him that she had a had a ‘severe shock’ in her ‘Anglican soul’ about pronouncing a benediction in his presence, he simply replied ‘it was the best blessing I have had since my mother died.’ (Bid Me Discourse, A.M.Royden Papers).

Maude was at the heart of the struggle for women’s ministry within the Anglican Church. In 1918 she had for instance spoken in Hudson Shaw’s church on the League of Nations and Christianity. As a result Shaw (who, in 1944, later married Maude after the death of his  first wife) was rebuked by the Bishop of London. Undeterred, in 1919 he again asked her to preach at the three hours’ service on Good Friday. The bishop forbade it, on the grounds that this was an especially ‘sacred’ service. Denied such space by her own Church, in 1921 Maude Royden consequently established the Guildhouse, as an ecumenical place of worship and a cultural centre. On Sunday afternoons there were talks about politics and the arts and she herself preached at the Sunday evening service to a congregation from all over London. In 1929, following the initial impetus given by women such as Ursula Roberts, she began the official campaign for the ordination of women when she founded the Society for the Ministry of Women. The first English woman to become a Doctor of Divinity in 1931, she made several worldwide preaching tours from the 1920s to the 1940s.

first wife) was rebuked by the Bishop of London. Undeterred, in 1919 he again asked her to preach at the three hours’ service on Good Friday. The bishop forbade it, on the grounds that this was an especially ‘sacred’ service. Denied such space by her own Church, in 1921 Maude Royden consequently established the Guildhouse, as an ecumenical place of worship and a cultural centre. On Sunday afternoons there were talks about politics and the arts and she herself preached at the Sunday evening service to a congregation from all over London. In 1929, following the initial impetus given by women such as Ursula Roberts, she began the official campaign for the ordination of women when she founded the Society for the Ministry of Women. The first English woman to become a Doctor of Divinity in 1931, she made several worldwide preaching tours from the 1920s to the 1940s.

Such pioneering work would have been enough for most people, particularly with the controversy it created. Yet Maude Royden did not restrict her Christian feminism to safe causes. For her indeed, Christian feminism was in fact true Christian ‘humanism’, a ‘democrac y of the virtues’, in which all were to be valued and empowered. Consequently she was also well in advance of many in her generous and sensitive treatment of sexual issues. Most notably of all, she gave passionate support to Radclyffe Hall when, in 1928, she published the novel The Well of Loneliness about the subject of lesbianism. Widely attacked as obscene and corrupting, the chief magistrate, Sir Chartres Biron, ordered that all copies be destroyed, and that literary merit presented no grounds for defence. Under pressure, the publisher agreed to withdraw the novel and proofs intended for a publisher in France were seized in October 1928. In the face of this, Maude Royden was unshrinking, and Radclyffe Hall therefore wrote to her with thanks, underlining her motivation for writing the novel:

y of the virtues’, in which all were to be valued and empowered. Consequently she was also well in advance of many in her generous and sensitive treatment of sexual issues. Most notably of all, she gave passionate support to Radclyffe Hall when, in 1928, she published the novel The Well of Loneliness about the subject of lesbianism. Widely attacked as obscene and corrupting, the chief magistrate, Sir Chartres Biron, ordered that all copies be destroyed, and that literary merit presented no grounds for defence. Under pressure, the publisher agreed to withdraw the novel and proofs intended for a publisher in France were seized in October 1928. In the face of this, Maude Royden was unshrinking, and Radclyffe Hall therefore wrote to her with thanks, underlining her motivation for writing the novel:

May I take this opportunity of telling you how much your support of The Well of Loneliness has meant to its author during the past months of government persecution. I wrote the book in order to help a very much misunderstood and therefore unfortunate section of society, and to feel that a leader of thought like yourself had extended to me your understanding was, and still is, a source of strength and encouragement.

Such incidents speak of a different kind of Christian faith in action as an expression of Christian feminism at its best. No wonder then that Maude Royden, like many Christian feminists, was critical of the Church’s attempts to respond to a changing world. The chief obstacle, as she saw it (as in The Hour and the Church, 1918), was the Church’s inability to be a true ‘fellowship’. Rather, she observed with feeling, it too often seemed obsessed with the definition of ‘orthodoxy’, or with getting people to ‘come to church’ as it were a musical concert. Even the efforts of reforming groups were all too often focused on the establishment. So:

Such incidents speak of a different kind of Christian faith in action as an expression of Christian feminism at its best. No wonder then that Maude Royden, like many Christian feminists, was critical of the Church’s attempts to respond to a changing world. The chief obstacle, as she saw it (as in The Hour and the Church, 1918), was the Church’s inability to be a true ‘fellowship’. Rather, she observed with feeling, it too often seemed obsessed with the definition of ‘orthodoxy’, or with getting people to ‘come to church’ as it were a musical concert. Even the efforts of reforming groups were all too often focused on the establishment. So:

To pass from a gathering of Labourists or Suffragists to one of, for example, ‘National Missioners’ was like passing from warm life to chilly death… At the one, all was staid and middle-aged, cautious and polite, with the extreme and chilling politeness of people who are too kind and nice to want to hurt one another’s exceedingly sensitive feelings, even if, in order to avoid this, it was necessary to avoid saying or doing anything to the purpose. At the other, all was alive and gay, hopeful and young. We were not afraid of hurting one another’s feelings, for we were all too much set on a great purpose to be thinking of our feelings at all.

Such words might all too often be descriptive of the difference between ‘live’ movements of our own day and many church meetings. For, as Maude Royden affirmed, the ‘hallmark of the living movement’ is not asking people to subscribe to particular writings or to recite particular beliefs, which only participation in the movement can bring home to them. All that is asked is acceptance of the ‘aims and objects’. In terms of the way of Christ: ‘Can ye drink of the cup that I drink of or be baptized with the baptism that I am baptized with?’:

Would it be safe? No, of course it would not be safe… we are afraid of such risks, afraid of such a terrible victory (as Christ’s)… we treat the Church as one long accustomed to ill-health. Do not open the window! Do not bang the door! You cannot take risks with the invalid. Step lightly, speak softly, at any moment the poor thing might die!

Instead, for Maude Royden, as for so many Christian feminists then and since, the Christian faith and journey to peace and justice were ‘the great adventure’. May God strengthen and inspire us to leave aside our own temptations to safety and to continue the journey today…

Prayer

God of all humanity,

We give thanks for Maude Royden

and for all Christian feminist pioneers.

We rejoice in their successes and gallant failures,

in their willingness to take risks, and to seek to use their gifts.

Grant that we too may be empowered by your love,

that we may play our full part in the great adventure of life and faith,

In the name of Jesus, who gave up his life so that we might all be free, Amen.

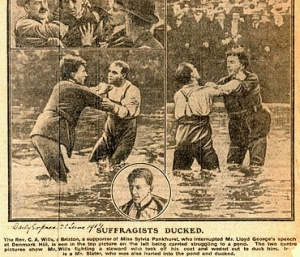

First-wave feminism was very much a movement of women. Yet, as seen in earlier posts, some men played a helpful supporting part. Whilst not to the same degree as many women, a few also clearly suffered for their involvement. This also helps highlight the obstacles of the struggle. Fear of loss of position, livelihood, reputation and support continues to act as a break on involvement in struggles for justice and freedom today. Thankfully, some are willing to transcend fear’s shackles…

First-wave feminism was very much a movement of women. Yet, as seen in earlier posts, some men played a helpful supporting part. Whilst not to the same degree as many women, a few also clearly suffered for their involvement. This also helps highlight the obstacles of the struggle. Fear of loss of position, livelihood, reputation and support continues to act as a break on involvement in struggles for justice and freedom today. Thankfully, some are willing to transcend fear’s shackles…

He stood alongside Sylvia Pankhurst and the East London Federation through all their tumultous activities of 1914, even when other good friends stood back. On one occasion for example, Sylvia Pankhurst planned a march to end at Westminster Abbey as an appropriate ‘symbolic’ act on Mothering Sunday (22 March 1914). Despite approaching the Dean in the hope of adaptation to the evening service no reply had been received. Arriving at the Abbey, led by C.A.Wills, in cassock and white surplice, the procession found the Abbey gates shut in its face. Undeterred by the profered explanation that the Abbey was full, Wills immediately declared that ‘then we will pray where we stand’. To the consternation of the clergy within, he then led an impressive open-air service (see accounts in Votes for Women 27 March 1914 and Christian Commonwealth 21 March.1914)

He stood alongside Sylvia Pankhurst and the East London Federation through all their tumultous activities of 1914, even when other good friends stood back. On one occasion for example, Sylvia Pankhurst planned a march to end at Westminster Abbey as an appropriate ‘symbolic’ act on Mothering Sunday (22 March 1914). Despite approaching the Dean in the hope of adaptation to the evening service no reply had been received. Arriving at the Abbey, led by C.A.Wills, in cassock and white surplice, the procession found the Abbey gates shut in its face. Undeterred by the profered explanation that the Abbey was full, Wills immediately declared that ‘then we will pray where we stand’. To the consternation of the clergy within, he then led an impressive open-air service (see accounts in Votes for Women 27 March 1914 and Christian Commonwealth 21 March.1914)

porter and generous backer of the

porter and generous backer of the  historical position of women, particularly in the Christian religion, and the theological and ethical rationale (or lack of it!). Such publications typically brought floods of appreciation and enquiries for more information from women of various denominations. Indeed, she played a considerable part in helping the Free Church feminist pioneer Hatty Baker find material for her own eagerly received work Women in the Ministry. Especially welcomed was her book Ecce Mater, which, in tracing early Christian history, made a powerful case for the opening up of church ministries to women. Fulsome tributes came in from all quarters. ‘We owe you so much’, wrote Emmeline Pankhurst for example, ‘for showing so clearly the real place of women in Christianity’. Other leading women campaigners such as Charlotte Despard then made wide use of the book in their speeches, whilst requests for precise references and further information increased.

historical position of women, particularly in the Christian religion, and the theological and ethical rationale (or lack of it!). Such publications typically brought floods of appreciation and enquiries for more information from women of various denominations. Indeed, she played a considerable part in helping the Free Church feminist pioneer Hatty Baker find material for her own eagerly received work Women in the Ministry. Especially welcomed was her book Ecce Mater, which, in tracing early Christian history, made a powerful case for the opening up of church ministries to women. Fulsome tributes came in from all quarters. ‘We owe you so much’, wrote Emmeline Pankhurst for example, ‘for showing so clearly the real place of women in Christianity’. Other leading women campaigners such as Charlotte Despard then made wide use of the book in their speeches, whilst requests for precise references and further information increased. her letter resonates with the kind of difficulties Christian feminist scholars still face today within the Churches, even when they are warmly received for their insightful and well-grounded work more widely:

her letter resonates with the kind of difficulties Christian feminist scholars still face today within the Churches, even when they are warmly received for their insightful and well-grounded work more widely:

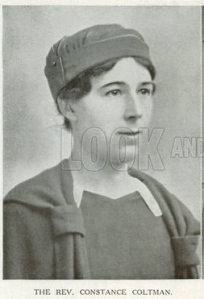

nd the interdenominational Society for the Ministry of Women. In the 1950s she even learned Swedish so as to support women seeking ordination in the Church of Sweden. A lifelong pacifist, throughout her active life Constance was also involved in peace movements, particularly as a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, as a vice-president of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and as one of the founders of the Christian Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

nd the interdenominational Society for the Ministry of Women. In the 1950s she even learned Swedish so as to support women seeking ordination in the Church of Sweden. A lifelong pacifist, throughout her active life Constance was also involved in peace movements, particularly as a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, as a vice-president of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and as one of the founders of the Christian Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

what the Prayer Book says about such requirements, and then to leave to them the responsibility.

what the Prayer Book says about such requirements, and then to leave to them the responsibility.

where she met prominent British and American suffragists and gave a number of speeches, as well as attending the World Conference of Woman’s Christian Temperance Unions. Back in New Zealand. she was then elected president of a new National Council of Women (NCW) of New Zealand. and later headed up the council’s newspaper, the White Ribbon (an international WCTU name and symbol which has a new dynamic role today in the worldwide, male-led,

where she met prominent British and American suffragists and gave a number of speeches, as well as attending the World Conference of Woman’s Christian Temperance Unions. Back in New Zealand. she was then elected president of a new National Council of Women (NCW) of New Zealand. and later headed up the council’s newspaper, the White Ribbon (an international WCTU name and symbol which has a new dynamic role today in the worldwide, male-led,